Christopher Workman: Toppling the Blue Wall of Silence

Everyone knows that law enforcement is a dangerous profession. What most people may not know is that police officers are more likely to harm themselves than to be harmed by others. Compared to the general population, law enforcement officers face a 54% higher risk of dying by suicide.

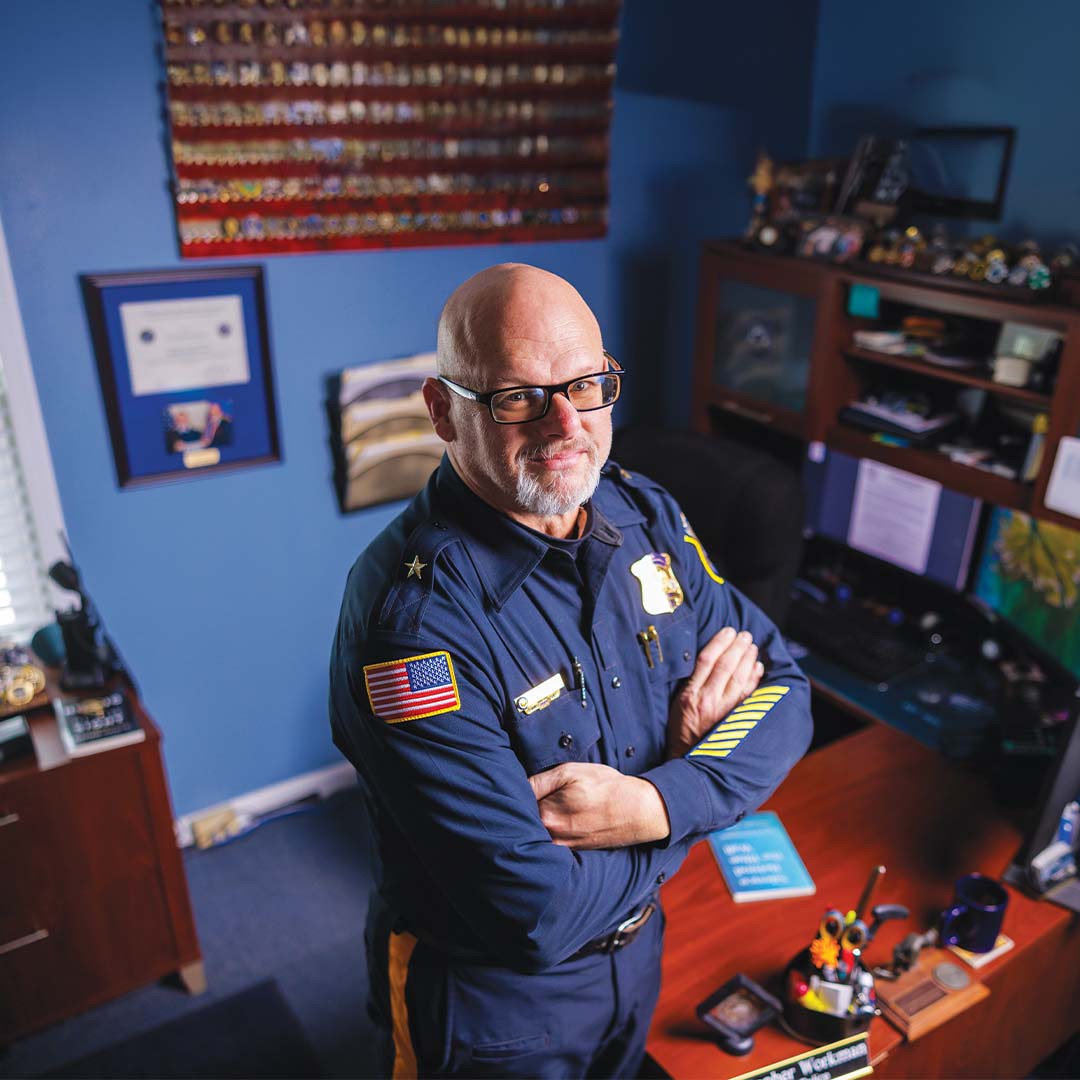

“It’s the nature of our job,” says Wilmington University alumnus Christopher Workman, who has been chief of police in Cheswold, Delaware, since 2013.

“We are constantly dealing with people on their worst day,” Workman says. “So we’re exposed to a lot of trauma, and that can cause emotional problems. You’re always on edge, and over the years, it gets worse, and you get to a point where you don’t trust anyone. You’re skeptical of everything.”

Another factor is easy access to firearms. According to CNA, an independent, nonprofit research and analysis organization, firearms were used in 82% of public safety personnel deaths by suicide.

But perhaps the most critical factor, Workman believes, is “the stigma over mental health.”

“We are in a profession that demands that we ‘be a man’ and ‘suck it up’ when it comes to revealing our emotions,” says the veteran of 24 years in law enforcement and 30 years as a first responder. Sometimes, he says, officers believe that talking about their mental problems will cost them their jobs.

“As a result, we remain silent. That’s what leads to alcoholism. That’s what leads to pills — things to help us forget. And sometimes, that leads to suicide.”

Workman is speaking from experience. He suffered his own emotional crisis in the winter of 2023. “I had a lot going on,” he says. “I had stress at work. I had stress at home. Not through anybody’s fault, but things were kind of falling apart all around me. This was after years of fighting these feelings. And I just wanted to stop the madness.”

He was home — alone except for his two dogs — when his despair and anxiety became overwhelming. He went outside and began walking in circles in his driveway, trying to block out the thought of ending it all.

Luckily, he didn’t have immediate access to a firearm. “I don’t take a weapon home,” Workman says, “because my wife doesn’t like guns, and I have a young kid in the house. It may seem odd for a police officer to never leave a gun in his house, but I’ve never been a gun guy. It’s a tool of my job. I’m proficient at it, I use it, but I don’t bring it home.”

He didn’t have a plan, and he didn’t have the means, but still, the thought was there. “Probably not having a gun at home saved my life,” he says.

He eventually went inside, sat down, and called COPLINE, a 24/7 hotline staffed by trained volunteers who are retired law enforcement professionals.

“You find out you’re not by yourself,” he says, “and that helped me start to get back on track.”

Almost as soon as he set off on his journey to mental wellness, he began thinking about how to help fellow officers dealing with similar problems. He says “the psychiatrist thing” and anxiety drugs didn’t work for him, but talking about his problems did.

In 2022, he earned a WilmU degree in Behavioral Sciences with a certificate in Emotional Intelligence and Leadership, so he had an educational starting point for such conversations. After conferring with officers he had befriended at police conferences, Workman decided to start a podcast.

The DeepBlu Project began last June. Its mission is to provide listeners with thought-provoking discussions about PTSD, police officer suicide, occupational trauma, and overall officer health and wellness. Workman conducts the podcasts from his home in Middletown and usually has guests with wellness or leadership experience. By the end of last year, he had produced 19 episodes.

At about the same time, he started writing a book. He had developed the habit of keeping notes — mini-journaling — throughout his career, and that became the basis for “Silence Behind the Blue Wall: Surviving the Mental Health Stigma in Police Culture.”

Published last September, the 113-page book is meant to help

law enforcement officers navigate the emotional demands of their profession “and build resilience in the face of adversity.” Drawing on his experiences, Workman challenges his fellow officers to prioritize their mental well-being and build resilience. To

help them, he presents practical tools and techniques, such as meditation, mindfulness, journaling, exercise, creating a support system, and therapy and counseling.

“The book is a quick read, and it’s officer-friendly,” he says. “It was written to let officers know that they’re not by themselves and that it’s OK to not be OK, but it’s not OK to stay that way.”

He emphasizes that maintaining your mental health as a cop requires constant work. “It’s a process that you need to go through every day — cleaning out your mental closet. It’s also important to never stop learning — to continually seek out resources and support.”

A native of Chester, Pennsylvania, Workman is continuing his education by pursuing a WilmU master’s in Administration of Justice with a concentration on Leadership and Administration. He’s scheduled to graduate this summer.

As a result of the DeepBlu Project and the book, many people have contacted Workman through Linked-In and other social media, and he has gotten several speaking gigs. “I haven’t been paid a dime for any of them,” he says, “but that’s not the point. If one person listens to the podcast, if one person reads the book, and it stops them from doing something and hurting themselves, that’s a win.”

Want to read more in-depth stories? Explore our latest magazine articles.