Henric Karlsson, club director at Kramfors Alliansen, Sweden, shaking hands with Juan-Pablo Bernal. sealing Juan’s first professional contract as a soccer player.

For Juan-Pablo Bernal, soccer — “the global game” — opened a door to the world. The urge to explore that followed led him most recently to spend nearly half a year in Central America, hiking, surfing, and trying to live like the people who live there. “I like the idea of getting away from our idea of what life should be like in North America,” he wrote in an email during his travels early this year.

“I like the idea of getting away from our idea of what life should be like in North America,”

That idea originated, in part, on a playing field on WilmU’s Route 40 playing field. “My entire life, ever since I was six years old, has been soccer,” says Bernal, who grew up in Toronto, Canada. “It’s a path that took me to Wilmington University. Coach Nick (Papanicolas) took a chance on me, and I’m grateful that he did.”

Bernal earned a bachelor’s degree in Sports Management in 2016. In pursuit of professional athletic opportunities, he played three seasons with a Swedish soccer club, which gave him the opportunity to travel in Europe. At first, he was apprehensive about setting out on his own. “Before, everything had always been organized for me — where I’d stay, what I’d eat,” he recalls. “But then I was bit by the traveling bug.”

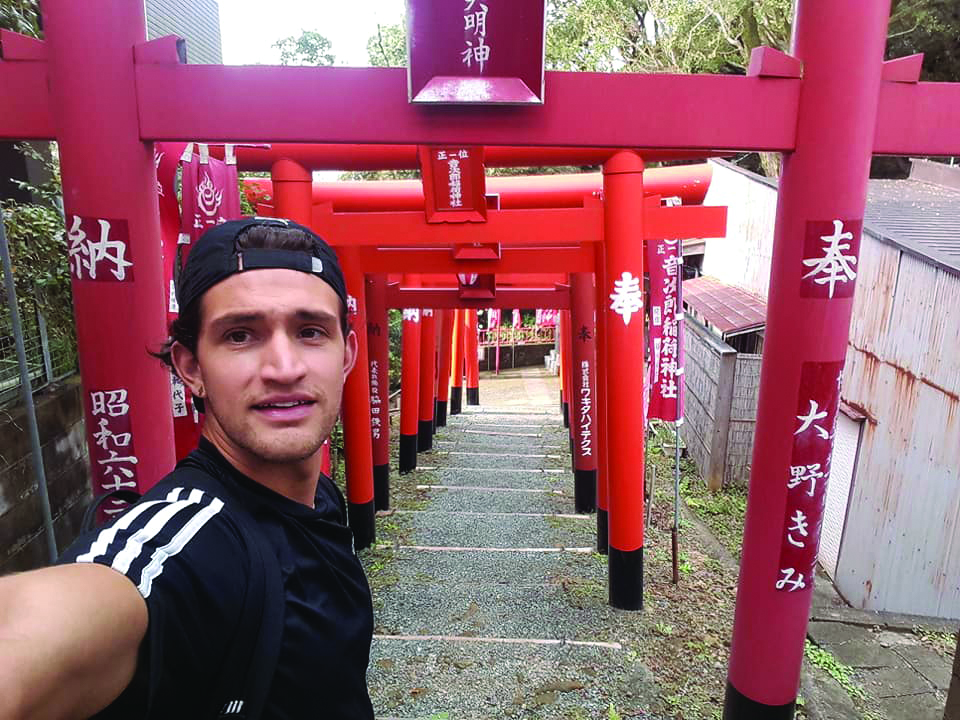

Hiking the Fushimi Imari, a temple with 1000 torri gates.

His conversations with fellow travelers inspired him to book a month in the Philippines to learn how to surf. He ended up roaming around Pacific Asia from September 2019 through February 2020, also visiting Saipan in the Northern Marianas Islands, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam.

“I was already thinking about Central America even before I left Asia,” says Bernal, who arrived in Costa Rica in November 2020. He’d learned a lot about travel since his time in Sweden. “I improvised. Wherever I could go, I went. I’d make a plan, but I might not stick to it. It was better to be flexible.”

Carrying all of his belongings in a 70-liter backpack and riding local buses or hitchhiking from city to city, Bernal stayed with host families he’d met through an app on his phone and camped in backyards.

“The only way I largely ever afford to travel,” he wrote alongside one of the many photo collections he posted to social media, “is like this: I volunteer or work, cook and eat in a hostel and avoid tourist traps like $100 zipline rides, taxis and American chain restaurants.”

By February of this year, he ventured into Panama. He spent two weeks with an indigenous community at their remote mountain-forest reservation. He tasted iguana, avoided scorpions, and washed his clothes in the river. “Some of the houses had an electrical outlet,” he says. “It would take an entire day to charge up one of my devices.”

He also stayed with a Colombian-Danish couple building a bakery and restaurant. “In exchange for some of the best meals I’ve ever had,” Bernal wrote on social media, “I help them out in the garden, or with some basic construction (I have no idea what I’m doing).”

Juan-Pablo has been photo journaling his trip on Facebook. The trip looks fascinating.

A picture of me and a friend on a hiking trip in Norway, where we had no where to bath except in the 8 degree Celsius sea water.

Guatemala followed in mid-March with “Mayan ruins, an island with flower-colored buildings, an active volcano and a black sand beach where all the surf is happening.” His camera was out of commission by this point, so there are no pictures.

“I actually felt relieved that I was freed of the pressure to produce photos and obsessively check for reactions,” says Bernal, who admits to developing mixed feelings about social media by the end of his journey. “Why are we constantly checking instead of living?”

He surfed Mexico’s Pacific coast for a few weeks in April and May before flying to Miami, then finally returned to Toronto in June. But the dry season in Colombia is coming up in December, and he’s wanted for a long time to get to know the country of his birth, to meet the family members who live there, to see how other people are living.

“Anywhere I go, I come back with a different mentality,” he says. “I would encourage people to do their own versions of what I’ve done.”

-David Bernard